BLOG

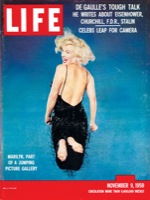

23 November 2006 - M. Monroe of Antarctica

Have you ever met with those black and white photos shot during Marilyn Monroe's visit to American troops in Vietnam? If it happens to you, take two minutes to look over them: she is wearing a short chenille jumper, she has got short and curly hair, a porcelain skin and a changing smile... all the requisites to be a Venus at that time and not only... The soldiers are fanning out around her, quite close to the photographer too, so that you can look at their faces: heads stretching in every direction, pale-blue, with short and very tidy hair, wide open eyes, emaciated but smiling faces. Have you ever met with those black and white photos shot during Marilyn Monroe's visit to American troops in Vietnam? If it happens to you, take two minutes to look over them: she is wearing a short chenille jumper, she has got short and curly hair, a porcelain skin and a changing smile... all the requisites to be a Venus at that time and not only... The soldiers are fanning out around her, quite close to the photographer too, so that you can look at their faces: heads stretching in every direction, pale-blue, with short and very tidy hair, wide open eyes, emaciated but smiling faces.

It is a perfect moment, come out of the photomagician's top hat. It talks about men in an infernal circle, about their impulses, sure, but also about their very human desire of normality and beauty, that, at least for a while, can snatch them from a too hard routine. She, Marilyn, slung there, in the Asiatic jungle, directly from the USA. Looking at that photo, I guess how it ran: the wait of previous days, the confirmation, the denial, then the organization to carry her safely, the officers' greeting, the soldiers' attempts to have a chat...In short, life at the base was upset, for one day, by the event. She, tiny in the middle, is looking, listening and answering, but with her mind away, far, unattainable.

I know I risk fans' and geologists' anger if I say that here, in Mc Murdo, it is a star: the drill core. OK, OK. I know it makes you laugh, but consider it a provocation, not as surreal as it may seem. They have been waiting for years, they minutely studied every detail, not only regarding the choice of the site, but also its cataloguing, its care; they even established real keepers watching over it 24 hours a day. They are the "curators". Moreover, they sharpened every possible way to hear every syllable it will deign to pronounce in all the ways it knows: colour, thickness, consistency of sedimentary strata, microscopic fragments of fossils, composition and shape of clastic pieces, even the cracks and the fractures are recorded and interpreted in a maniacal, obsessive research of every possible feature. Concentrating all there, in a few centimetres width, in a cylinder of rock, mud and water. Because, let us be clear, in the end it is nothing more and nothing less than this... Hoping to read and interpret it correctly (see further explanations by ANDRILL research teams).

Certain and immediate is its lunar beauty and surely inexplicable everything researchers can get. It is a beauty that leaves nobody unmoved, you in Italy least of all, considering your e-mails about the images of the cores published. Two weeks ago our star arrived at last, troubling, from a very democratic point of view, every ANDRILL member's life here at the base. Among the settlements adopted by the troop there has been my passage to night work. Actually, I have been working for some days and I rest in daylight. Because of the bewilderment Italy-Antarctica, I live and work according to your own rhytms there, even if most of our team live 12 hours before me.... or maybe after me and before you? Or after you and before them..Goodness knows! Let us say that there is a little temporal confusion, mixing, pleasantly, with the spatial one. These days I have got another proof regarding how cores direct the rhytm of our lives. In fact, last days the drlling stopped because of the need to change the drill bit. Thanks to the equation no drilling - no cores, they decided, guess? one day rest. It was the right moment for the traditional business trip and so it was. Some kilometres far from the base, there are some of the most important historical sites. We placed in little groups and like good tourists (our turn by night) we visited Schackleton's hut - expedition 1907/1909 - and Scott hut - expedition 1911, the one made famous by the challenge, tragically lost, with Amudsen. One of the two huts was near a penguins' area, and we had to have a look. So I prevent you from saying that I was in Antarctica and I saw no penguin... I admit they are as enchanting as adaptive creatures. It was a colony of a thousand individuals, Adele species, black and white, almost all lying towards wind and protecting their themselves.

But it was strange: the natural side, except the landscape, did not impress me at first. If you remember one of the first passages, where I talked about explorers, imagining them on a chair with a cup of hot coffee... well, I visited authentic historical places, where probably that scene really happened. I saw the chairs, the cups and the spoons I imagined. But also wool socks, egg-shells, sleeping-bags (real ones), oilcloth trousers, the smell of fat seal and horse. I can say I was wrong. I must confide: what does not scan, and I cannot imagine, is how they could live all there, the time of an expedition which, at that time, normally lasted two years. They arrived in summer, the whole winter (dark for 4 months and a temperature of -30°C), they rested there and the second summer started the real expedition:

4 months;

by foot, with some dogs or horses;

towards the South Pole (1400 km)

and return.

During my return, in the warm of the tracked vehicle, I made another effort to understand: the home road was a beaten track on the Ross platform, equal to the distance run by the explorers in a good day walk. Distance: about 35 km; time, at maximum, possible, speed: 2 hours! How can it be? Nothing to do; even maths repels my attempt to understand hard work, endurance, determination, dreams, ideas...yes, ideas and dreams...

4 November 2006 - TRIP TO CASTLE ROCK

Saturday evening, in the laboratory, before a pc. At about 8 p.m. I try to remember the last time I turned it off, but I don't manage. Bad sign. After a while, Julian, my New Zealand teachmate, comes in with an uncoded, catatonic look. We look at each other, we laugh and (maybe) we do not even say. Silently we go out of the laboratory and we know: tomorrow we are going to Castle Rock.

The environs of Mc Murdo offer good chances to have some brief healthy trips. There is only one problem: here we are in Antarctica. It counts little if you live in the most equipped and comfortable base of the continent; as soon as you go out, it is the master. And, we have understood, it does not joke. During recreational activities, accidents, due to different causes, are not unusual. Some of them, unfortunately, did not have a happy end. In order to solve the problem, rigid rules were established. One: whoever goes in for outdoor activitites has to follow a specific course (just 3 hours).  Two: before the departure, you have to state the exact data (way, start, arrival, participants etc.) in a dedicated area of intranet, the informative net of the base. Three: right before leaving the base, you have to go the firemen's barracks for the final permission, given according to the weather forecast, and for the emergency radio. At about 11 o'clock, we succeed in finishing the scheduled liturgy and, dressed like divers, we walk towards Castle Rock: a rocky formation emerging in the middle of Ross Isle, at 5 km from the base. It is the longest route and during the return we reach Scott base: 16 km, 6 forecast hours. After half an hour walk and a brief stop in an emergency refuge (called "the apple", for its shape and colour), we reach Castle Rock. We feel well and we decide to go along the road towards the top. And we do well. The top is flat and without snow, the rock is brick red, porous and friable, with big fragments of black rock, many of which vacuolar. I pronounce the name Franco told me: 'ialoclatsiti'. Probably, the fruit of a remote lave flow in the ice. We look around and we find nothing like what we have seen before. Two: before the departure, you have to state the exact data (way, start, arrival, participants etc.) in a dedicated area of intranet, the informative net of the base. Three: right before leaving the base, you have to go the firemen's barracks for the final permission, given according to the weather forecast, and for the emergency radio. At about 11 o'clock, we succeed in finishing the scheduled liturgy and, dressed like divers, we walk towards Castle Rock: a rocky formation emerging in the middle of Ross Isle, at 5 km from the base. It is the longest route and during the return we reach Scott base: 16 km, 6 forecast hours. After half an hour walk and a brief stop in an emergency refuge (called "the apple", for its shape and colour), we reach Castle Rock. We feel well and we decide to go along the road towards the top. And we do well. The top is flat and without snow, the rock is brick red, porous and friable, with big fragments of black rock, many of which vacuolar. I pronounce the name Franco told me: 'ialoclatsiti'. Probably, the fruit of a remote lave flow in the ice. We look around and we find nothing like what we have seen before.

Heavy and low clouds quickly follow the profile of the volcano Erebus, parts of others, taller and more laminar, draw shadows moving over the ice towards a horizon that joins white and azure in every possible way, according to the direction you look at: white/azure, white/sky-blue; white/white... We sit down. We stay and watch silently for half an hour, just like we did a few hours before in the laboratory. Then, lazyly, we take our cameras and take some shots. In the meanwhile, the wind is blowing, rather convincing in inviting us to descend and we do not take much persuading.

GROUND MEANS - Wednesday 1th November 2006

Lots of you ask me news about the base, everyday's life and the relation with the environment. I do have many things to tell you, trust me, and I have got a lot of material too, I just lack some time to publish it. Moreover yesterday we started to work in the laboratories and for 4 hours a day we help researchers in their analytical job on cores.  But be quiet: I will find time anyway. Today, for instance, I would like to open a particular window about life at the base. Do you want to understand the connection between man and his environment? Let's start from an unusual point of view. Let's do like this: we will observe at close quarters the means used in ground shifts, the ones they use here everyday. But be quiet: I will find time anyway. Today, for instance, I would like to open a particular window about life at the base. Do you want to understand the connection between man and his environment? Let's start from an unusual point of view. Let's do like this: we will observe at close quarters the means used in ground shifts, the ones they use here everyday.

The antarctic equivalent of our buses, utes, undergrounds and motortrucks that we have use and fight daily. Have you ever guessed? Perhaps a new idea will raise from the environment and, why not, also from the men that built and now drive them.

They impressed me at once, all of them. As soon as I reached the base. It seemed to me as if I was in a fun-fair where everybody tries to outdo each other in driving the oddest means. Each one queerer than the other, that would stir everybody's imagination: long and tall spiders, big lizards with huge eyes, wide and very flat turtles, iguanas with a long muzzle.... only the thought to classify them causes a headache.

But all, without distinction, have one thing in common: a cable, with a dangling tap coming out of the front bonnet. There is an electric circuit heating the engine in the parks, that, as you can see, are all equipped with current.

As far as I know I am not the only one suffering cold.

THE SNOW - Sunday, 29th October 2006

Two nights ago it snowed. They were thin and microscopic flakes. I let them fall on my jacket to watch them better. They were infinitesimal points. The most expert asserted that they were not carried by the wind, but new, just shaped. Right before sleeping, I looked out: there was a layer of 3 cm, light like a veil. The following morning there was no more sign of it, not even in the most sheltered places. Everything was like before, as if nothing had happened.

Since we were children, we learned to associate the idea of cold with that regarding snow; the colder it is the more abundant it snows. Then, at school you learn that Antarctica is the coldest continent of the world and in a moment you begin dreaming about how much snow it can fall there: 3, 5, 10, 100 metres of snow, insurmountable and massive walls by which you invent impossible exploits shortly before falling asleep in the rainy nights of March. The very moment of the year you have to put aside definitively the expectation for new snowfalls.

"In Antarctica that does not happen.." you think, "..in Antarctica children are always happy; they watch so much snow falling down!" But it is not so. "In Antarctica that does not happen.." you think, "..in Antarctica children are always happy; they watch so much snow falling down!" But it is not so.

In Antarctica it falls far less snow than you usually think. On the coast a little more, but on the inland very little: the equivalent of 2,5 cm of water. It is surely less than that on the top of our Alps. What is very strange here is that snow, simply, does not melt.

Never.

Here the life of a snowflake does not resemble our home-grown snow. Instead, it is like the grains of sand in the desert. It falls, sure, but then it rises, thanks to very violent winds, it travels along boundless distances, beats against stones and rocks, frosting them like glass, it mixes with grains of sand, then, sometimes, it settles, in order to rise again and continue its pilgrimage.

Melting, a fancy, that is clear, but it can be entrapped and accumulated under other snow. At that moment it starts getting compact under the weight of overhanging snow, flakes get closer and the empty spaces reduce until, after about one thousand years and at about 80 m deep (Italian-French project EPICA), it becomes real ice, solid, very hard. That is its destiny, but only more immediate, as it has not come to an end yet.

Ice does not stay still; it moves radially from the centre to the exterior, just where it has to go: to the ocean, where else? But it arrives slow, very slow, in a surreal slowness, exasperating, irritating. Hundreds of thousands years. Hundreds of thousands....I do not know what you think about, but slowness arouses dread, awe, respect, much more than speed... slowness evokes the cosmos, that cannot be stopped. It manages to make useless and a little droll the rest, man and speed included.

Maybe proceedings here are like this, in this bubble where everything is broadened, expanded and where a simple cycle of light is spread on 365 days.

Antarctice! Sunday - 22th October 2006

Antarctica! Here I am, I am here, no doubt. Sometimes I feel a little giddy, I let myself to be carried by a voice telling me "It is not true, it is not true!", then it is enough to go out and breathe some fresh air and the one out there waiting for me brings me to reality.... If they call cold what I have known till now, here they should call it another way. I do not know how, maybe ipercold, ultracold, freeze or, better, you should find a new name, like antarctice. If you have any suggestions, please send me. It is an important matter.

Yesterday it was -29°, without considering the wind. I look for a sign letting you know, the clearest way, what means lesstwentyninedegrees and I find it at once: the doors! I think you recognize something familiar in the photo. Have you ever entered the kitchen of a restaurant or the backs of some butchers' shops? No? Well, try; you will find cold stores. Places for the preservation of food at several degrees. About twenty years ago in every house there were freezers with a hook. They are still trendy and you can find them in some glamour houses on retrò freezers. Here in Antarctica the doors are like those ones. And I assure you they are not there for show. Yesterday it was -29°, without considering the wind. I look for a sign letting you know, the clearest way, what means lesstwentyninedegrees and I find it at once: the doors! I think you recognize something familiar in the photo. Have you ever entered the kitchen of a restaurant or the backs of some butchers' shops? No? Well, try; you will find cold stores. Places for the preservation of food at several degrees. About twenty years ago in every house there were freezers with a hook. They are still trendy and you can find them in some glamour houses on retrò freezers. Here in Antarctica the doors are like those ones. And I assure you they are not there for show.

They say during the first days you suffer more because the organism has to accustom itself. Well, I say: let's hope so as, for the moment, I admit, I quite suffer cold... It seems to me there is really nothing you can wear to feel a little better and leave the cold out of your body, far away. I can try to wear one of those doors...

Up to now, in two days stay at the base, I have been out there, in all, a quarter of an hour, not more. I assure you it is sufficient and more than that. Every time I go out and just before opening the door I secretely hope to be a bit more prepared than previously and every time I get immediately disillusioned. It is enogh to walk for some metres. And I wish I had already touched the door-handle. The cold comes from the end of my trousers, grazes my face, my cheeks, my ears and I feel it everywhere and instantly: strong, invincible, mysterious. Besides it has another ally here: dryness. In the air there is 1% humidity creating effects which I must speak of before long. For the moment, be satisfied with the noise of the snow under your feet.

The different places of the base are few metres away from each other and you have to dress and undress to go to one another. Let's do the accounts. Outside -29°C, inside + 15°C: a difference of 44 degrees. It is as if you moved from the top of Mt. Cervino, in an evening of January, to a square in Agrigento at one o' clock p.m. in mid-August. This happens every time you pass that door. Problem 1: how to dress? I would go around the base with a little trolley, ready to dress every time, but maybe it is not very practical...what do you think about? Then I try several combinations of strata, but no solution is satisfactory for me. Too much warm inside and, above all, too much cold outside. When I am there, beside clenching my teeth and cheating myself that next time it would be a bit better, I always have one fixed thought: past explorers, their wool cotton, leather and fur clothes, just seen at Christchurch Museum (you will be informed also about that). They used to spend several months at these temperatures, even whole winters, without any external help. I imagine them so much that I almost see them, in cotton tents, with red faces, crouching on wood stools with a metal cup of steaming coffee.

I get silent.

Antarctica has just started teaching me who it is.

I listen to it.

Silently.

|

|